Take Us to the Snow

When I was five years old, my dad promised to take me and my sister to the snow. We lived in a suburb of Los Angeles, and the idea of snow was as foreign to me as the idea that people lived anywhere but California; I knew it in the abstract, but when I tried to solidify it in my imagination, it dissolved like so much mist.

The memory of my dad promising to take me to the snow is one so old that I don’t actually remember it anymore; it has been repeated so often over the years that it has the cemented certainty that oral tradition imbues a story. Long after it became clear that my dad would never take his daughters to the snow, the memory of that promise served as something to throw in his face any time I needed to remind him of his failings as a father.

“Remember how you promised to take us to the snow?” went the refrain, delivered with pointed accusation. It was a rhetorical question, not meant to be answered by that point in our lives. We were too old for snowmen and sledding.

He often met us with misdirection.

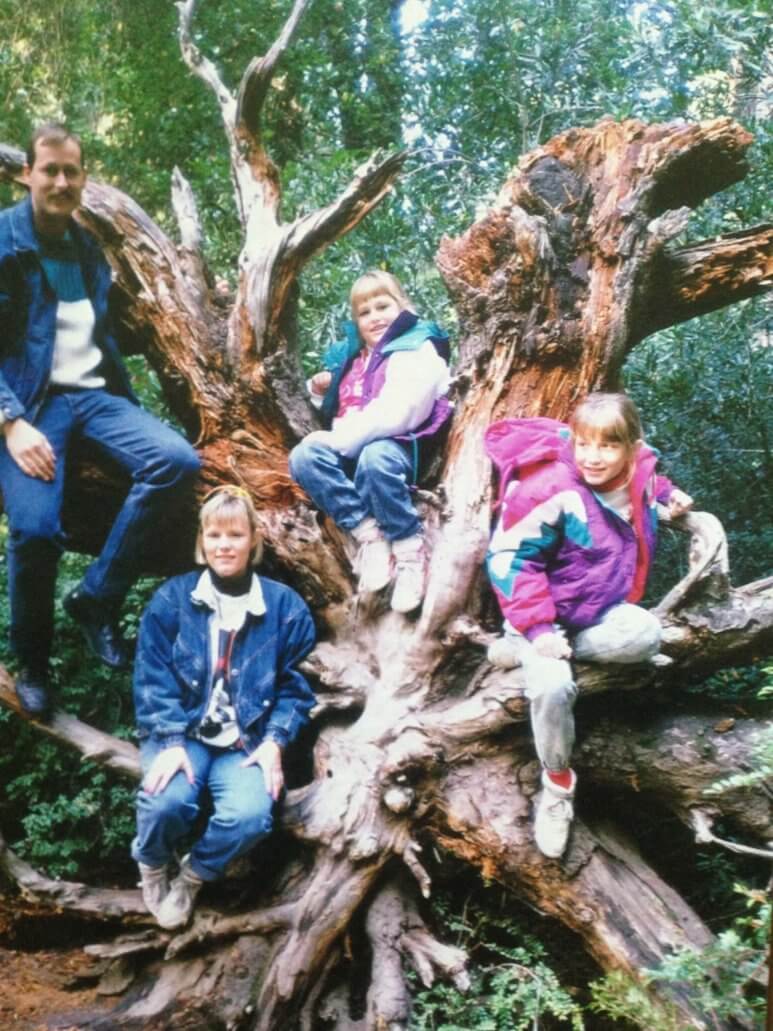

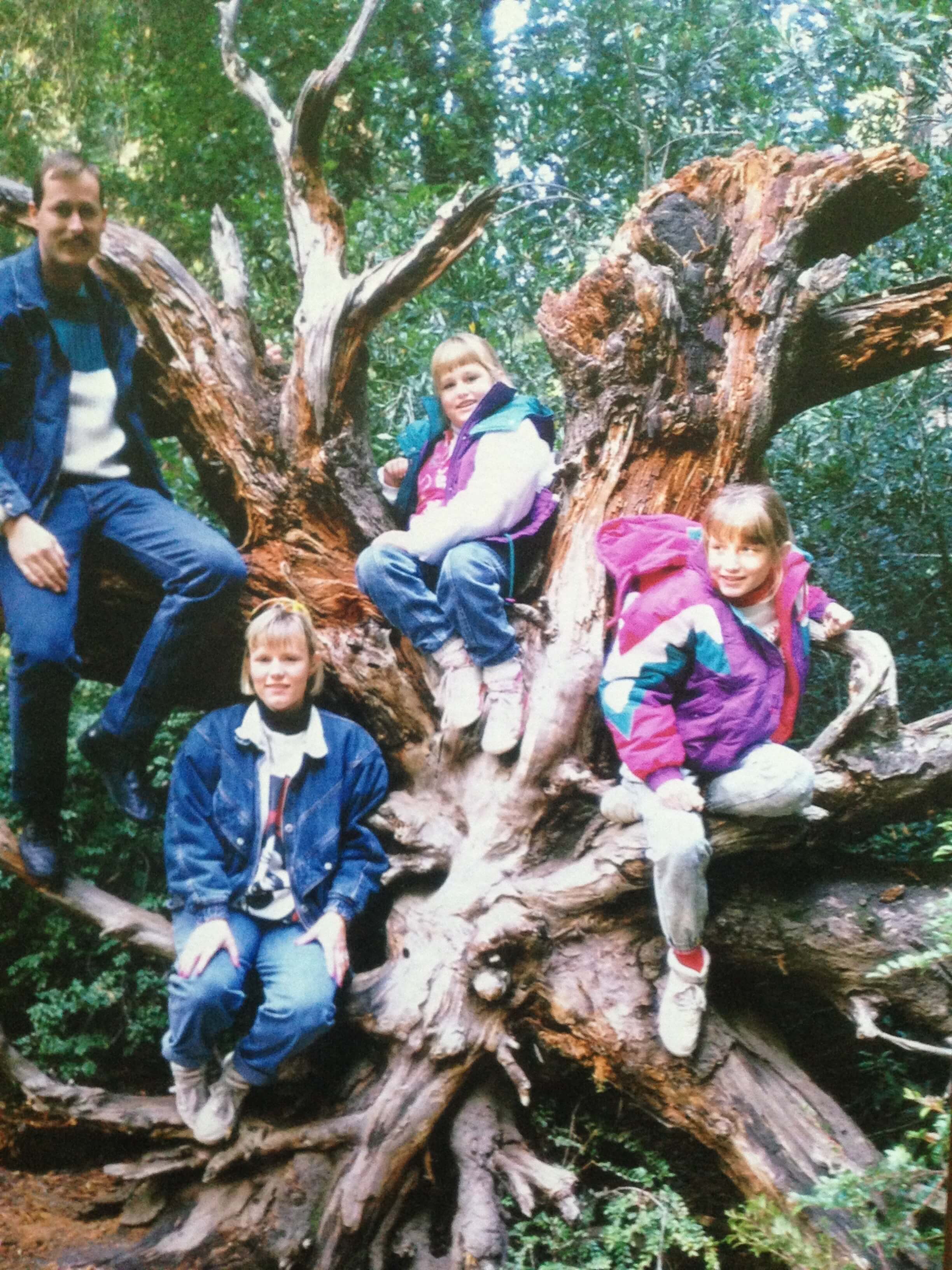

“Well, I took you to Big Basin, and we saw the redwood trees, trees older than Jesus. That’s better than snow, if you think about it.” His eyes would widen as he asserted this judgment, an icy blue color that never failed to frighten me with its intensity. We all had to admit that the redwoods were pretty spectacular.

But they weren’t snow. How cold was snow, and how did that cold feel when held in your hand? For the first ten years of my life, I believed snow had the dry consistency of powdered feathers, not realizing it was wet. I also believed it tasted slightly sweet, as if dusted with sugar before being sent down from heaven. Would making snowballs be as easy as it looked in the movies, with the snow clinging to itself in a perfect orb? What would it feel like to fall into a soft patch of it, to bury myself in a blanket of white?

– – –

Despite my longing for vacations that didn’t involve dirt or extra work, my dad used to take us camping. He taught me how to chop wood with a real axe, and how to build a proper fire that stayed lit as long as you cared for it. He took us hiking, which I grew to love in spite of my innate laziness and preference for reading above any other activity.

One particular hike, when I was ten years old, found us in Yosemite for the first time. Everything about the place enchanted me: the smell of fresh air, the scale of everything in Yosemite Valley so garishly gargantuan, the sound of tourists speaking languages I had never before heard spoken aloud. Everywhere you turned, the landscape seemed woven with magic of an ancient place, its own magnetic sphere drawing crowds from around the globe.

That day we were hiking to the top of a waterfall. My younger sister Emile complained every step of the way, as was her custom, and lagged behind with my mom, whose legs weren’t as long as mine and my dad’s. I always took the lead on these hikes, bounding ahead with a sense of adventure married to a conflicting desire to please.

As a girl in the middle of a major growth spurt and the onset of early puberty, I took my hunger seriously. When my empty stomach made itself known, I alerted everyone to the time.

“Should we stop and eat? It’s lunchtime.”

My dad protested. “Let’s wait until we get to the top of the waterfall. I bet it’s getting close.”

We agreed, and reshouldered our packs before continuing.

A half-hour passed. An hour. We began whining. My step lost its bounce, and took on the trudging quality of a journey to Mordor. We asked for our sandwiches, only to be told, “Just wait a little longer.”

Two hours. We begged for our trail mix.

Three. We ceased asking. It wouldn’t have done any good, anyway.

At three thirty, we still weren’t at the top of the waterfall, but at that point we reached an outcropping of stone overlooking the spray. My dad dropped his pack.

“Let’s stop here.”

We all pulled out our sandwiches (mine without cheese and mayo, of course), and gratefully devoured them.

“Wasn’t it worth the wait? We didn’t get to the top, but this is exactly where we’re supposed to eat.”

We all agreed that it was, whether we believed it or not.

– – –

I finally saw snow for the first time on that trip. Though it was August, that day we were in the high country, where the tree line thinned out and the air felt impossibly devoid of weight. As we hiked along a smidge of a lake so clear we could see to the bottom, patches of snow decorated a corner where the ground butted up against the peak of the mountain.

“Look! It’s snow!” we shouted, running over to it, a tangle of awkward limbs and bouncing fanny packs.

I sunk my hand in. It was crusty. It was cold. It was wet. We stomped around in the little patch, with initial pleasure at seeing our hiking boots outlined in the crisp, squeaking white.

It soon felt oddly deflating. Crunching around in a snow mound that was smaller than my bedroom; during August, dressed in my patterned shorts, felt wrong.

“See girls? I told you I’d take you to the snow,” he said.

I stuck up my chin. “This doesn’t count. It’s not real snow.” We jumped off and headed back to the trail.

“You still owe us.”

He still owes us.

7 Comments

chaman asgar

I liked reading your story.

Jen Brunett

So sweet. What adventures you had! I would love to see those trees. I’d certainly trade you for our snow!

Jen Brunett recently posted…All For Them: Breaking the Chains of Anxiety

Lance

This reminds me of my family trips to the North Georgia mountains, similar stuff. My parents owe me a lot…lol.

Lance recently posted…Dumb – Lessons Learned From Montage Of Heck

Ellen

In our family lore it is the clubhouse Dad was going to build. I don’t actually remember that promise never kept (I think I was too young), but there were plenty of others like it.

Ellen recently posted…Opportunity

Cyn K

I like what is left unsaid, how the snow stands for so much more.

Cyn K recently posted…dine and dash

Get free iPhone 15: http://asoyinsaat.com/uploads/go.php hs=29c5396669772b3e26a8aa8ce284195c*

8ty403

You got 45 255 USD. Gо tо withdrаwаl > https://telegra.ph/BTC-Transaction--617752-03-14?hs=29c5396669772b3e26a8aa8ce284195c&

4l5waz